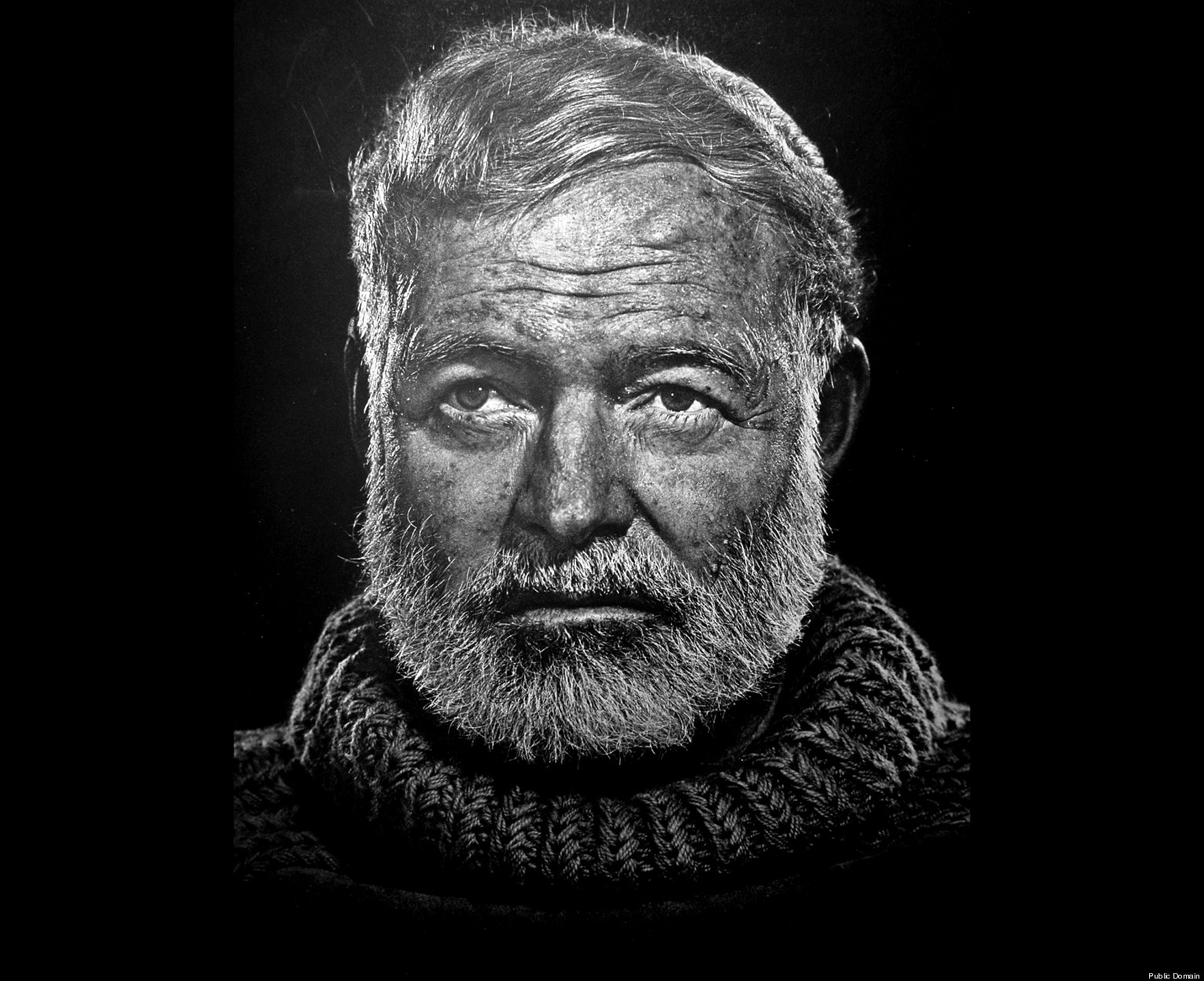

The widespread yet varying attention drawn by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s “Hemingway” documentary series — which ran its course on PBS last week — proves, if nothing else, that its subject still lingers in the world’s collective consciousness almost a century after his first books were first published.

While Ernest Hemingway may no longer dominate the literary scene as he had by the middle of the 20th century, the mystique of his public and private lives resonates into the 21st.

If one had to name American writers from the previous century with whom younger generations of readers are most fascinated today, the list wouldn’t start with Hemingway, but (at least off the top of my head) with James Baldwin, Joan Didion and Toni Morrison. Even Flannery O’Connor, also the subject of a recently aired PBS documentary, has come under greater scrutiny in recent years if only to assess some of the racist sentiments found in both her letters and in her vivid, acerbically comic depictions of Southern life.

Suppose there’s anything upon which literary critics and general readers can agree when it comes to Hemingway. In that case, it is this: his use of language is what endures and influences more than any other attribute of his work. The Hemingway style — clipped, allusive, laconic and hard-boiled — helped give American writing its rhythm and tone as much as blues and jazz helped give American music its global identity.

In language and life, Hemingway’s style reads like a metaphor for what it means to be an American, for better and for worse. Our inability to let him go speaks less to what we encounter on the page and more to what lurks behind it — about Hemingway and us — that we alternate between revelling in and wanting to unsee.