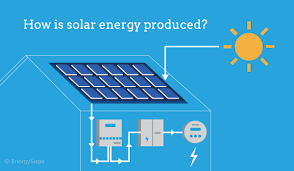

As a boy, Dayne Goodheart has considered the sun. He’d found out that its power turned into being harnessed to power spacecraft and was surprised about such technology ability on Earth.

His interest grew over the years, as did that capability. As an adult, Goodheart vowed to apply solar energy to help free his Nez Perce reservation for a reliance on dams and different old power reasserts that threatened the Idaho tribe’s way of life. Jasmine Neosho got here to a comparable awakening later in life. She was operating as a bar supervisor in Chicago while the Dakota Access Pipeline protests erupted on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation in 2016.

Neosho, a member of the Menominee Nation in Wisconsin, sympathised with activists’ fears that the pipeline could threaten the Dakota regions’ water delivery and sacred burial grounds. Frustrated from feeling something like that, she said it couldn’t make a difference that drove her to move back to school — and returned to the Menominee Reservation – to get her friends degree in herbal resources.

But being a Goodheart, father of three children in his early 30s and Neosho32, the way toward’s a sustainable future is riddled with obstacles.

The green monetary growth that promises many Americans a brand new access to the middle class hasn’t lifted every person equally. The fields are so unique that connecting employees with schooling opportunities is difficult. Plus, what education exists frequently fails to resonate with Native people, focusing on technical abilities rather than environmental expertise and cultural practices.

As a result, inexperienced-collar jobs are ruled by white men, with many low-earnings people of colour both blind to the possibilities or unable to get entry to them. Roughly three-quarters of green-collar jobs – fields starting from water conservation and sustainable agriculture to solar-panel setup and resource-efficient construction – are held by men. White people account for greater than 4 of 5 positions in the sector, consistent with a 2017 study.